I saw James Ellroy in the flesh on June 6th. He was giving a reading of his new book LAPD ’53 to benefit the Los Angeles Police Museum. It took me close to two and a half hours and four bus transfers to do it. As he’s one of the literary gods that I cut my teeth on and soured my mind with, it was more than worth the time and the expense it took to make it happen.

The sprawl of Los Angeles is seemingly endless. Hot stucco. Dry 1950s woodwork. Sunburnt cars parked in front of modern strip malls and professional buildings that refuse to get with the goddamned program. Different neighbourhoods offer varying levels of threat. But the bus felt safe. I saw few white people riding. My travel companions were were largely Latino women of an age I was unable to determine. Their skin cured by the sun, they could have been in their thirties or on the cusp of sixty. A group of them, friends either through work or neighbourhood, got on together and sat, talking trash and passing around a copy of a magazine amongst themselves as we trundled on, insulated by air conditioning—a temporary balm against the 36 degrees Celsius heat that lurked just beyond the glass and steel that surrounded us. An old man boarded with a cold, sweating gallon of milk. I wondered how warm it'd be by the time he got it home.

The Los Angeles Police Museum is housed in the department’s former Highland Park Police building: Thrown together in 1925, It’s a Renaissance Revival sort of deal that holds on to the heat long after the sun goes down. It’s gorgeous, but it’s cinch to see why the LAPD moved into better digs back in 1983: Too damned hot. Too few windows, too little space. The building was restored to its original condition when they opted to use as a museum, after getting kicked around by water damage, vandals and general neglect. Once inside, the smell of the woodwork takes you back to a time that your brain tells you was better, but anyone with a passing knowledge of history will confirm to have been just as nasty, if not more so than the societal quagmire we’re currently stuck wallowing in. The walls are lined with photos of the LAPD’s fallen, old hardware and methods of policing that have fallen into myth.

Perhaps forty people paid one hundred bucks to come and hear Ellroy speak. The event was held on the building’s second floor: a wide open space that I’d bet cash money was used as a detective’s bullpen back in the day.

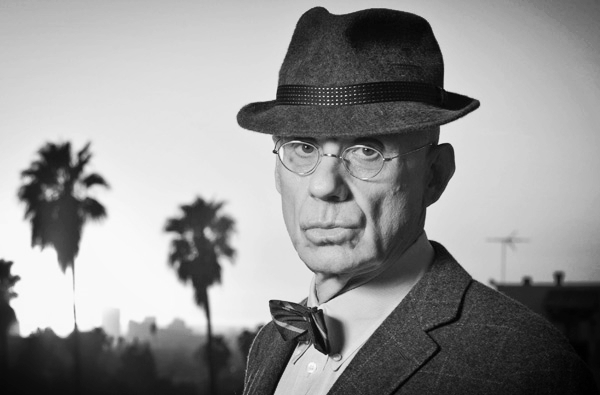

Ellroy, as usual, was a beast, or so he pretended. He faced his congregation wearing a blue blazer, Hawaiian shirt, white slacks and cream coloured running shoes--an outfit thrown together by a blind yachtsman. Tall, wide, but at sixty-seven years old, frail, you could still see that he must have been an imposing piece of meat when he was younger. Loud, demanding attention and articulate, he was everything I’d seen in interviews on the web and TV. But when Glynn Martin, his co-writer on LAPD ’53 took centre stage, I watched Ellroy as he noshed on a piece of catered pizza. Crouched over in his chair, focused on his grub and seemingly elsewhere in his head, he was a far cry from what I’d just seen howling the pages a book at us a few moments before.

This was not a man who craves attention.

After the reading, I was fortunate enough to talk to him. Again, Ellroy showed me something new. Neither withdrawn in the wings or a madman at the fore of the room, he was chatty, friendly and fiercely intelligent. I told him that when I was thirteen years old, the hometown’s local library refused to let me take out The Black Dahlia because I was too young (years later, when I re-read the book, I discovered they were absolutely right.) So, I stole it, read it and, when I was finished, jammed it in the after-hours returns slot. I’d never stolen anything before in my life. It was, in turns, both terrifying and exhilarating. And while I was too young to truly grasp the full horror of what the book contained, the notion that it was forbidden to me made reading it seem that much sweeter. Ellroy lit up as I laid the tale out for him, and told me that when he was around the same age, he too swiped a book a librarian didn’t want to let him away with.

“She said it was full of sex,” he sez to me. “It wasn’t.” It was a pulp sci-fi novel. More’s the pity that I can’t remember the name.

I’ll tell you, I got what I came for.

I wasn’t there for the signed copy of LAPD '53 that I walked away with, although it’s great to have it. And it wasn’t for the bragging rights to have met one of the great monsters of modern American literature. I wanted to catch a glimpse of the true character of a man who’s writing has coloured my work from an early age. I’m not stupid enough to think I gained a window into Ellroy’s soul, and I wouldn’t dare say that I know the man’s mind. But being able to spend a few hours in the presence of a master of my craft and trade stories with him; to watch him wear the various masks of his profession, and perhaps, briefly, catch a peek of what he’s like when he’s off the clock? That’s a hell of a thing.

And as far as a souvenir goes, the memory is a far cry better than anything else I could ever hope to bring home from my time in Los Angeles.